Childhood and education intrinsically possess a strong dichotomy: they have been a part of social organisations and of human thought since ancient times, whilst also being strongly influenced by the cultural environment at hand.

Despite the crucial role played by this stage of growth, the traditional perception across the two shores of the Eurasian continent somehow indicates a shared perspective on childhood that is anything but positive. In fact, childhood was intended as a stage that needed to be overcome – preferably in the shortest time possible – through appropriate education.

In classical Greek culture, and subsequently in Roman culture, children were not considered as active members of society, precisely because of their not fully developed personality: for this reason, the main concerns most pedagogues concentrated on was the educational process, which was the prerogative of both the family and the community. As early as the Roman period and at least until the arrival of Christianity, children were accepted only if mentally and physically healthy, because they were considered the working hands for the poorest families and continuation of the lineage for the richest.

In a similar vein, traditional Chinese culture considered offspring as a natural continuation of the patrilineal family and was aimed at shaping the “ideal child” through a complex system of moral precepts and ritual practices. In China, references to the phases of childhood and youth, as well as to social conventions that pertained to education, intended as moral cultivation, have very ancient origins and have been transmitted throughout the centuries thanks to texts such as Memoirs of Rites (Liji 禮記) or Rites of Zhou (Zhouli 周禮), which described the ritual ceremonies in use during the Zhou Dynasty (c. 1045–256 BCE). While canonical texts and behavioral norms have played a constant and crucial role in shaping children’s original characters, the development of educational theories and practices throughout Chinese history has also been deeply influenced by endogenous and exogenous doctrines such as Daoism, Buddhism, Christianity and Western thought.

Although characterized by a variety of reflections on the nature of childhood and on the approach to moral formation, the different Chinese and Western pedagogical traditions are often based on shared precepts and values, such as the universal duty of obedience, the virtuous example of fathers and teachers, the role of female figures in the early stages of a child’s life, while children’s nature is constantly referred to as raw material to be shaped, or as “tabula rasa” of Aristotelian memory. Moral and literary education is therefore not only aimed at developing the nature of the child and at completing his transformation into an adult, but above all has social purposes: since the dawn of Chinese thought, the pedagogical discourse has in fact always been intrinsically linked to the political one and to the improvement of society.

The formation of young people has an undeniable connection with the construction of the future of the community, although the tendency to look at the past in an uncritical way is not without the risk of producing inefficient or counterproductive pedagogical methods. Despite this apparent contradiction and thanks to their predominant role in the Chinese intellectual debate of the last two millennia, the theories produced in various periods by the main intellectuals, who contributed to the discourse on childhood and education, provide a privileged point of view to study political issues, philosophical and social aspects of the history of China, while putting them in conversation with Western ones.

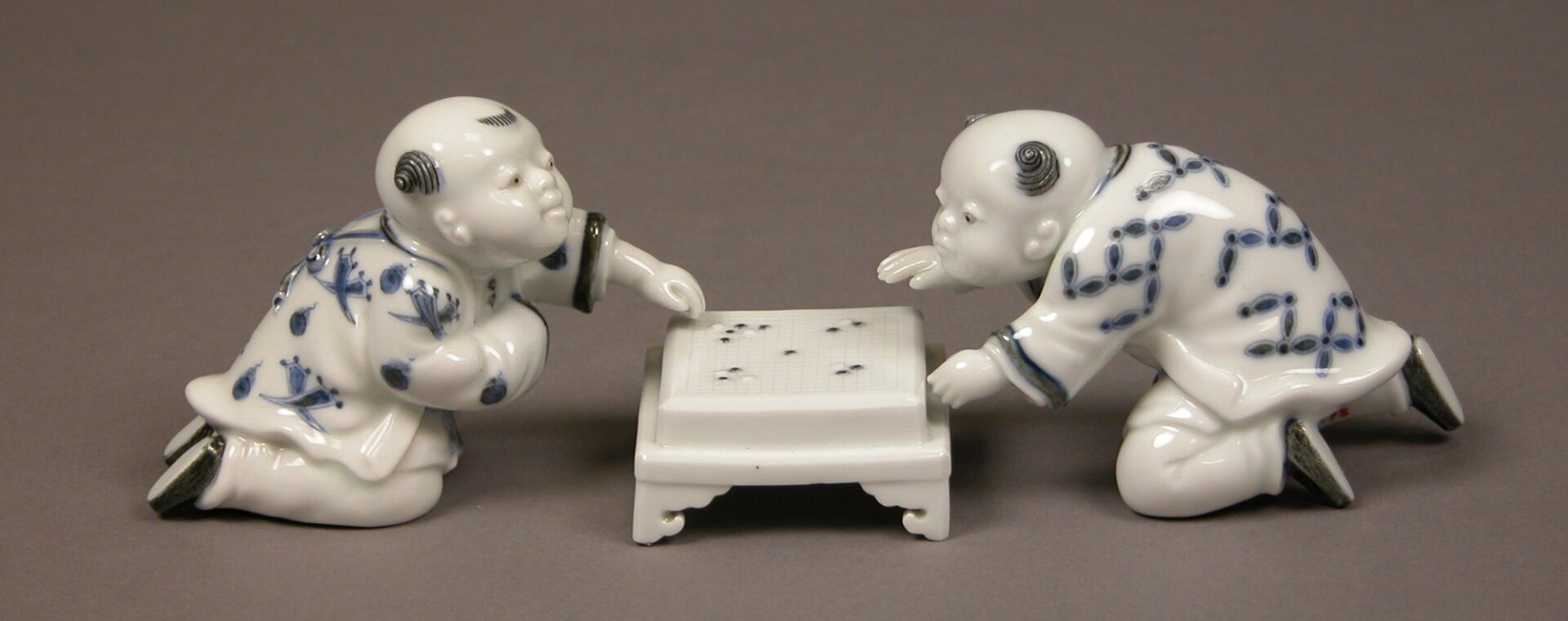

Wikimedia.

Building on these premises, this research project aims to retrace the changes in the representations of childhood and the practices of education in Chinese history, to examine which precepts and customs survived different forms of government and which instead underwent reconfiguration. Special attention will be paid to the contribution that external doctrines, particularly coming from the West as canonically understood, made to the pedagogical system of late imperial China and the early years of the Republic. The overall purpose of this multidisciplinary research, whose analysis is based on a variegated corpus of primary sources – including philosophical-pedagogical treatises, historical works, didactic texts, periodical press and examples of visual arts – is to explore how young people’s moral formation was designed and implemented in light of encounters with external elements and changing historical contexts, while at the same time demonstrating how the scope of education in China was perceived to extend beyond individual children and households as a pillar which guaranteed social order.

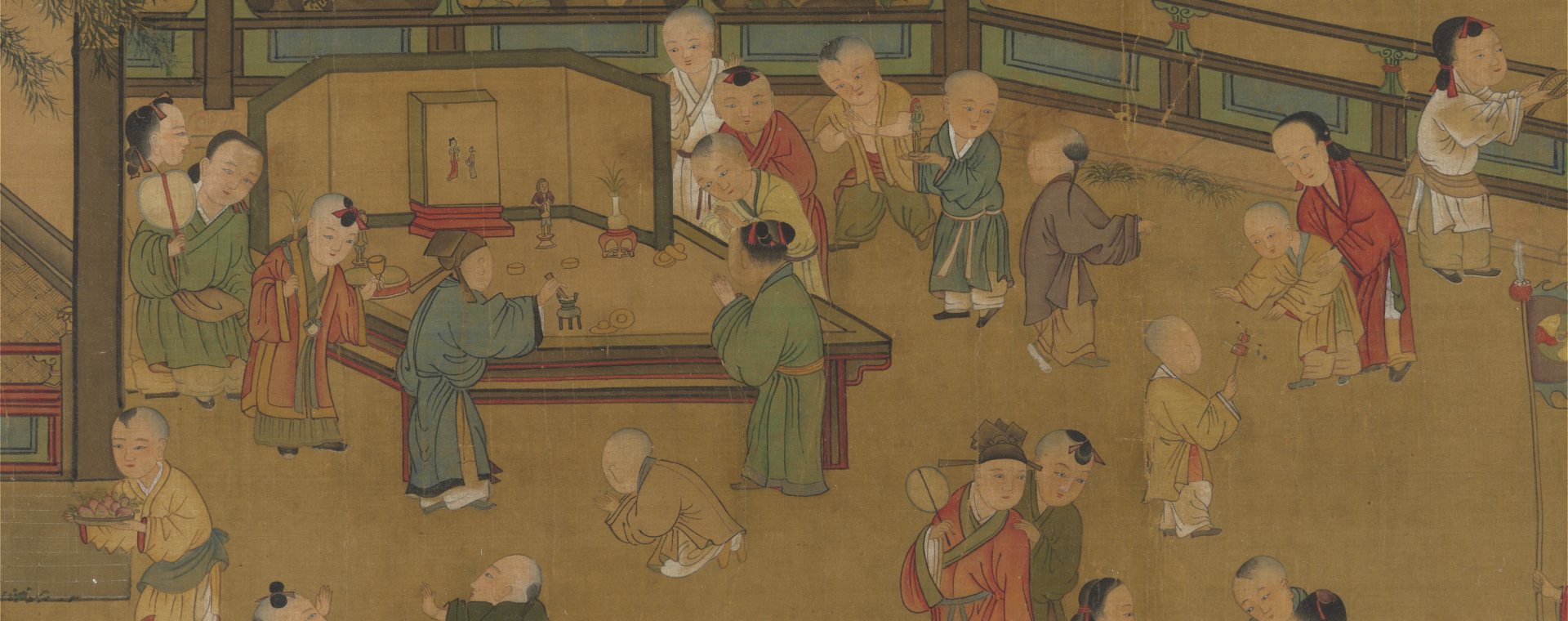

Children Playing, Unidentified artist (16-17th cent.).

The Met collection

Institutional project webpage at Oxford University Website: https://youthinchinesehistory.web.ox.ac.uk/youth-chinese-history